The crop of personal computers available in the last decade of the 20th century were markedly faster, more capable, and more connected than their primitive ancestors. Clock speeds and transistor counts were rapidly increasing, and the decreasing cost of memory and storage was opening up new avenues for the personal computer to evolve from an expensive desk accessory into a tool for multimedia and professional graphics design.

In 1991, the Intel i486DX was one of the hottest processors on the market—literally. It was one of the first that all but required a heatsink, and a cooling fan was a good option for processors with higher clockspeeds. But for Apple, the PowerPC architecture was still below the horizon, leaving just one choice for high-performance Macintosh computers in the early 90s: the Motorola 68040 microprocessor.

What a beast. The '040 was a substantial upgrade over the '030 that had previously been used by Apple. It featured 1.2 million transistors, over four times as many as its predecessor. This processor increased the L1 cache size by a factor of eight to 4096 bytes, and it was the first 68k processor to have an on-board floating-point unit (FPU). While not without its drawbacks, the '040 processor was an obvious candidate for Apple's next line of premium workstations at time. And this line would become known as “Quadra,” starting with the Quadra 700 and 900 models in late 1991.

While the floor-standing tower Quadra 900 was the crème de la crème in regards to overall performance and upgradability, its physical size and price tag were a barrier to entry for some. Its desktop size brother, known as the Quadra 700, was arguably the more impressive of the two computers anyway. After all, it was the Quadra 700 that featured in Apple's Quadra television commercial and went on to appear prominently in a certain Speilberg dinosaur-action blockbuster.

Both computers were marketed towards professionals looking for a home or office-based workstation-class computer, ideal for scientific, business, and design applications.

Fast forward nearly 30 years, and today the Quadra 700 is one of the most sought after vintage Macintosh computers. Part of this may be due to that supporting role next to Jeff Goldblum, but there are other reasons, too.

The 700 is one of the few vintage Apple computers to use tantalum capacitors on the logic board, rather than electrolytic. The latter capacitors inevitably leak electrolytic fluid, causing electrical instability and corroding traces on the logic board. Tantalum capacitors have no electrolytic to leak and are not prone to failure.

Other quality-of-life improvements over its peers include the Quadra's dedicated video RAM (VRAM), which is coupled tightly with the processor. A direct access to the frame buffer significantly improves video performance on the Quadra over other models like the IIsi. Memory expansion capacity was also improved, with the 700 supporting up to a total of 68MB of RAM. This amount was not possible at launch, as the SIMMs that supported this memory density would take several more months to be developed. VRAM could be upgraded to as much as 2MB.

I know all this because I remain a hopeless computer tinkerer who happened to come across a Quadra 700 around the start of 2020. Unlike my road test of the IIsi for Ars back in 2018, the Quadra 700 presented a tantalizing opportunity to really push the limits of early 90s desktop computing. Could this decades-old workhorse hold a candle to the multi-core behemoths of the 2020s? The IIsi turned out to be surprisingly capable; what about the Quadra 700 with its top-shelf early ‘90s specs?

-

Beware, some gear lust may result from reading about and look at a Quadra 700 in 2020.Chris Wilkinson

-

Still quite a handsome bit of hardware for the home desk.Chris Wilkinson

-

How long before Apple at least does some one off vintage styled hardware? How has this not happened in the last five years?Chris Wilkinson

Project Quadra 2020 (or, how I spend my time during a pandemic)

The 700 was sold to me in working condition, but otherwise “as-is.” There were a few items that could require immediate attention, not least being the floppy drive. Sticky, hairy, dirty—these were all common symptoms for Apple floppy drives with their doorless design even then. Over the years, this design decision naturally allowed all manner of dust and grime to build up. A full restoration of the drive would have to wait for another day, though, as I had plenty of spare drives to use in the meantime.

Half-assembled, I confirmed that the Quadra powered up just fine. Apple recommends not running the 700 for longer than 20 minutes with the case off, otherwise the passively cooled 68040 processor melts down. Not the best design, but it works fine with the case shut.

Vintage Macs usually require a full teardown and capacitor replacement before they can be safely powered up. The aforementioned electrolytic fluid and underperforming capacitors can cause all sorts of electrical havoc if a thorough cleaning and capacitor replacement isn't performed. With the tantalum capacitors on the logic board, the only real concern left was the power supply. A good dusting with compressed air blew out most of the large chunks of dust. The larger capacitors inside the power supply will need replacing eventually, too.

At this point, we had a working system with a modest amount of RAM and VRAM, a decently sized hard drive, and three empty expansion slots. As far as restorations go, everything went very smoothly. With no leaking capacitors or failing lithium batteries to deal with, the Quadra was in tip-top shape. This would be more than adequate for playing a few rounds of Bolo.

I think we can do better, however.

-

An open door policy, not the best for keeping hardware clean.Chris Wilkinson

-

Expect a little cleaning to be on the to-do list for anyone refurbishing vintage Macs these days.Chris Wilkinson

-

A happy place for many an Ars reader.Chris Wilkinson

-

Dated 1990, so this chip may have exceeded an Apple engineer's wildest expectations.Chris Wilkinson

Pimping my Quadra (but also trying not to break it)

If trying to modernize a machine like this, maxing out the RAM and VRAM is a logical upgrade. To bring the system up to a total of 68MB of RAM, I went online and purchased four 16MB 30 pin SIMMs. The 700 comes with four megabytes soldered to the logic board, bringing the total up to 68MB. This is not only plenty for most 68k-based applications, but it also allows for a generously sized RAM disk (should you need one).

Since the floppy and hard drive caddies needed to come out for the upgrade, I also went ahead and bought a total of six 256KB VRAM SIMMs. With 512KB already on the logic board, this brings the VRAM up to its maximum supported 2MB (2048KB).

Adding VRAM to a Macintosh did not necessarily improve performance, but it did enable more color depth and higher resolutions. With 2MB of VRAM in the Quadra, I would be able to use my “two-page” 21 inch display at 1152x870 resolution and with 256 colors, a very respectable setup. Lower resolutions such as 832x624 enable thousands or even millions of colors.

The Quadra 700 supported Macintosh operating systems all the way up to Mac OS 8.1, the last version that ran on Motorola processors. Mac OS 8 added a lot of cosmetic features such as desktop pictures and the 'Platinum' interface. In 1998, Mac OS 8.1 introduced the HFS+ file system. HFS+ (or Mac OS Extended) was not superceded until 2017 with APFS, introduced with macOS High Sierra (10.13).

Apple included an Ethernet port with the Quadra series for the first time, but there’s one massive caveat. The port uses the AAUI (Apple Attachment Unit Interface) standard, meaning that a dongle transceiver is needed to mechanically convert this socket into something more familiar, such as 10BASE-T and the 8P8C (RJ45) connector. Of course, Apple sold their own version of transceiver as did many other companies.

Despite the interface issues, this was still a big deal for home computers of the time. With in-built Ethernet as standard, there is no need to fill a NuBus slot with a network controller card. Apple baked in drivers for their on-board Ethernet from System 7 onwards, meaning that getting online is a breeze. The OpenTransport extensions and TCP/IP control panel were able to negotiate DHCP settings with my modern router, and pretty soon I was out on the information superhighway.

Macintosh computers had built-in SCSI support since the Macintosh Plus. Data transfer rates are a little pokey when compared to today, around 5MBps theoretical and much less in practice. Daisy-chaining SCSI devices is a cinch, so it wasn't long before my Quadra was upgraded with a 4x Apple CD-ROM drive, 1GB external hard drive and an Iomega Zip 100 drive. While making these changes I also replaced the smaller internal hard drive with another 1GB, for a total of 2GB in hard drive capacity.

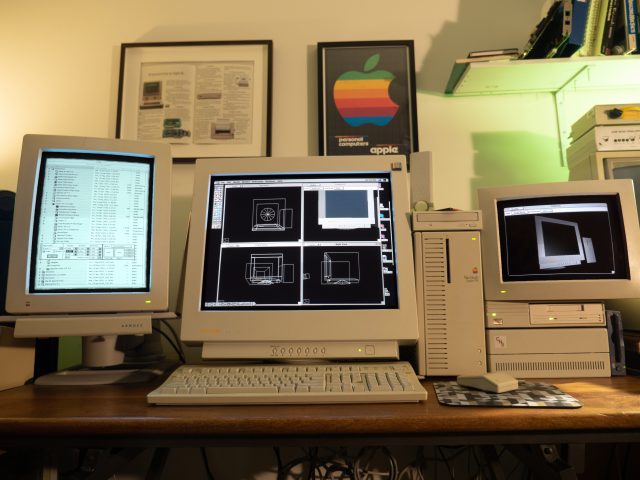

The NuBus interface supported the aforementioned network cards as well as a plethora of video cards. I happened to have an Macintosh 24-bit 'Display Card' handy, and in the midst of writing this story, I found myself pining for a second monitor. Apple's display card naturally supported the Apple Portrait Display, so before long I was using two absurdly large CRT monitors with the Quadra 700. Happy days.

If money and time were no objects, there are several more improvements that could be made. Adding a Fast SCSI bus is an option with NuBus, as is adding accelerated high-resolution high color depth video. The Quadra 700 can be overclocked from 25MHz to 33MHz with a touch of soldering and a new oscillator, bringing performance much closer in line with the updated Quadra 950 and its successors. PowerPC upgrade cards for the Quadra and Mac II line were also very popular.

So for now, my pandemic project is not the most powerful Quadra 700 out there, but it's not far off the pace.

-

What kind of things can you do today on a ~30-year-old computer? We'll have to Google that, I guess.Chris Wilkinson

-

Perhaps a little city building is in order?Chris Wilkinson

-

Picking out a perfect wallpaper is crucial, so...Chris Wilkinson

-

...luckily the Quadra is a designer's dream, still.Chris Wilkinson

-

I went ahead and bought a total of six 256KB VRAM SIMMs. With 512KB already on the logic board, this brings the VRAM up to its maximum supported 2MB (2048KB). And while adding VRAM to a Macintosh did not necessarily improve performance, it did enable more color depth and higher resolutions.Chris Wilkinson

Benchmarking the Quadra 700

There are some obvious tasks that are still well suited to the 700, or even older computers like the Macintosh II series. General office tasks such as word processing, database entry, and the like are well within its capabilities. The pimped-out Quadra 700, with its extra VRAM and larger system memory, makes these tasks a complete and effortless breeze. The high screen resolution of the Quadra 700 reduced my eye strain when compared to using something smaller, such as the Macintosh SE.

Vintage computers are well suited as distraction-free workspaces, and the extra performance of the Quadra 700 makes this particularly intriguing. For example: a lightweight word processor, such as Microsoft Word 5.0, is lightning fast and a true pleasure for just... writing. No cloud, no templates. You’re presented with just a blank page and some basic fonts.

While multitasking is definitely possible, the technology of the day only supports cooperative multitasking, meaning programs are at the mercy of other programs when it comes to handing off processor resources cleanly and on time. It's good enough, but preemptive multitasking was just a few years away with PowerMac (that would be a night and day improvement).

These basic capabilities are further supported by a decent network interface. FTPing to another local computer allows easy document backup and retrieval. Email applications such as Mulberry are still just as useful today, just make sure to set up your IMAP and SMTP correctly and you're good to go. As I did with IIsi, I even used Mulberry to talk back and forth with Ars Technica editors for this story.

The extra horsepower of the Quadra 700 came in especially handy when it came to Web browsing. For testing purposes, I used both Netscape Communicator 4.04 and Microsoft Internet Explorer for Macintosh 3.01. Both of these browsers were snappy enough to use, however there's still no easy way around modern Internet security protocols. Any site using https is strictly off limits for these browsers, shrinking the usable Web significantly. The websites that do load, however, can be surprisingly responsive. Proxy services such as theoldnet.com are a simple way to load websites as they were from various years past (using the resources of archive.org, and removing SSL to just make it work). Loading the Ars Technica homepage from 2001 was a slog, taking several minutes to load in all the text and images and eating up a good chunk of memory.

In practice I was at least able to use these browsers to access sites like the Macintosh Garden to download new software and browse support forums. While the Quadra 700 isn't capable of browsing the latest websites, it still supports a useful amount of Web content.

Things are really put to the test when the Quadra is paired with resource-demanding creative and business software. Infini-D (and its Backburner engine) for Macintosh 68k computers was an incredibly capable program for its time, arguably bringing studio-quality 3D rendering and animations to the home desktop. In an era when many professionals preferred Silicon Graphics workstations, the Quadra 700 was an intriguing option at a fraction of the cost.

Still, it's 25MHz. There's no getting around this, and making any meaningful comparisons to rendering on modern systems is an exercise in nonsense. The Quadra 700 takes 15 minutes to render a static test scene at 375x295 pixels, in millions of colors in maximum ray-tracing quality. On the 'shade fast' setting, it takes just 37 seconds, but that results in noticeably worse quality. On the 'shade best' setting, with shadows included, rendering the same scene took three minutes and five seconds with quite decent results. No doubt, the same operation would take microseconds on any modern platform.

Photo retouching in Photoshop had its limitations also. The JPEG standard is excellent from a compression standpoint, but it’s taxing on older processors. Loading a full resolution image from a modern DSLR can take an age, and making edits can be slightly painful. For touching up a basic 6x4 print, however, the Quadra definitely gets the job done. JPEG accelerators were a common sight in Quadra workstations of the day, and significantly improved the graphics design workflow.

Playing MP3s is definitely possible but don't expect to get any work done while the processor races to decode everything. It's still great to have the option of doing this even if the Quadra is just barely capable of being an MP3 player. It's much better as an AIFF player and can decode files into this format quickly if needed.

Full motion video is right at the edge of this system's limitations. The best results come when playing videos at a low resolution, low(er) frame rates, and making sure that videos are encoded using the Cinepak codec. All that means YouTube is not going to happen.

However, not all Cinepak codecs are made equal. I had best results when using a 'modern' PowerBook G4 and Quicktime to re-render videos using Cinepak, and then bringing these over to the Quadra. Don't bother trying to play anything but Cinepak video, it's just not going to happen. It also helps to have the video file inside a RAM disk, as the SCSI bus is another bottleneck for FMV. Many third party vendors such as Radius would later bring out NuBus cards that promised 30 FPS video at SD resolutions. In a TKyear commercial for the Macintosh Quadra, however, a smug-looking office drone somehow uses his snazzy new computer to watch some full motion video while working on a few other tasks. {Embed the TVC?}

What about the games? For vintage Macintosh gaming enthusiasts, the Quadra 700 is an excellent choice. Civilization II, which can make full use of my dual-screen high-resolution setup, is stunning on the 700. The turn-based action means that screen redraw time is less of an issue, and the CD audio is phenomenal. SimCity 2000 looks gorgeous with the same screen real estate and is more than playable. More than once, it was tools down for this author while tinkering away in SimCity.

Links Pro feels like it belongs on a workstation of this calibre, considering the demographics that would have been likely to afford such a speed demon. Again the nature of the game means that redrawing the scene after each swing isn't intrusive, and the gameplay is otherwise fast.

Wolfenstein 3D pushes the 700 right to its limits, much like full motion video from the previous benchmark. Definitely playable on a smaller resolution, the FPS that started it all gets choppy at 640x400. Later titles such as Duke Nukem 3D are far outside the capabilities for the Quadra 700, unless you're happy with a postage-sized playfield.

For any Macintosh games that were made at or around the early 90s, this computer is probably one of the best choices for playing them, especially with the extra memory.

It's a Unix system, I know this

So far we’ve only made passing reference, but no article mentioning the Quadra 700 could possibly ignore its starring role in 1993's Jurassic Park. In the film, Dennis Nedry wields dual Macintosh Quadra 700 computers at his workstation, alongside an SGI Crimson running IRIX. These computers were instrumental in Nedry's failed attempt at industrial espionage, leading to the destruction of the park (and far too many sequels).

Head canon is a funny thing, and it seemed difficult to justify why Jurassic Park's IT staff would mix Apple's desktop superstar with true Unix workstations. The odd pairing may be explained away if we consider Apple's A/UX operating system, though.

The Quadra 700 is one of a few Macintosh computers that can run A/UX 3.0, a Unix operating system spun off from AT&T's System V. This peculiar foreshadowing of Unix on Apple computers was mildly popular with hardcore computerists in the early and mid 90s. A/UX development stalled during the development of Copland and was later superceded completely by Unix-like Mac OS X.

Naturally, the 68040 processor in the 700 is a great choice for running Unix. For vintage system administrators that needed the most out of their metal, A/UX would have been an intriguing choice. Hosting a website using Apache or httpd is a cinch to get setup, and plenty of other Unix applications were compiled for A/UX during its operating life.

Completely covering the impact of A/UX deserves a story all of its own, but suffice to say it effortlessly elevated the Quadra 700 from Mac desktop to Unix workstation.

What does it all mean?

The Quadra 700 is one of the most impressive Apple computers of its time, but its true potential is only fully realized by investing in more memory and other basic upgrades. If you're a vintage computing enthusiast with mildly deep pockets, it's reliability and power makes it a great choice for some classic Macintosh gaming and nostalgia tripping.

But, obviously, the Quadra 700 is not going to replace your modern Mac or Windows system. New applications for the Motorola family of processors dried up during the PowerPC era, and the machine will always be hobbled by its technical limitations.

Despite these shortcomings, the Quadra 700 reinforced some of the same conclusions from my timing roadtesting a refurbished Macintosh IIsi some time ago. The gap between an '040 powered Mac and modern PCs doesn't feel nearly as wide as it should. This computer was released almost 30 years ago. On paper, it should be inconceivable that this can at all fit into a modern workflow. Present-day computers are gigascale monstrosities that should smoke something as old and plucky as the Quadra. And yet, they just... don't.

There's something intangible about these old computers that makes them a pure joy to use, limitations and all. At its worst, the Quadra 700 is a vehicle for unbridled retro gaming and a fun nostalgic afternoon. At best, it's potentially the clear frontrunner for some workflows, such as distraction-free writing and basic image retouching.

I would never go as far to say that the Quadra 700 should have a place on your desk. But step back, for just a moment, and appreciate these old computers for more than the sum of their parts. You may be surprised by what you find.

Chris Wilkinson is an Australian-based technology writer with an unwavering nostalgia for vintage computing hardware and obsolete electronics. He's previously written for Ars about bulletin board systems and the MacIntosh IIsi.

Listing image by Chris Wilkinson

Technology - Latest - Google News

December 11, 2020 at 07:30PM

https://ift.tt/2W4PI5d

Working from home at 25MHz: You could do worse than a Quadra 700 (even in 2020) - Ars Technica

Technology - Latest - Google News

https://ift.tt/2AaD5dD

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Working from home at 25MHz: You could do worse than a Quadra 700 (even in 2020) - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment